Quantum Information, Game Theory, and the Future of Rationality

Careful What You Look At: On Quantum Discord and Heartbreak Across Time

This post is somewhat different. It is not a typical technical essay, nor is it a movie review. Rather, it is an exploration of how the time-travel romance "Somewhere in Time" reflects ideas from quantum information theory and game theory. By drawing an analogy through the concept of quantum discord, I connect memory and strategic coordination—showing how even a fictional love story can raise real questions about decision-making and remembering.

7/10/20255 min read

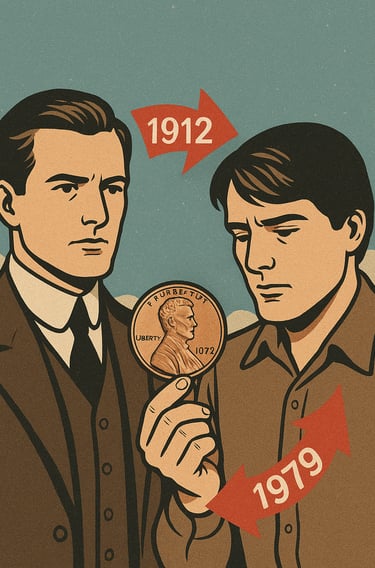

The 1980 film Somewhere in Time captivates audiences with its tragic romance between playwright Richard Collier (Christopher Reeve) and actress Elise McKenna (Jane Seymour), separated by nearly seven decades. Long after a mysterious elderly woman urges him to "come back to me," Richard becomes obsessed with discovering who she was. He eventually learns she was a famous actress in the early 1900s. Using self-hypnosis, he wills himself back to the year 1912 to meet her. Their love story unfolds in an idyllic past—until a small, accidental detail breaks the spell: a modern penny in his pocket, which he looks upon. Just seeing it is enough to shatter the illusion, and Richard is violently pulled back into his own time, never to return.

The first time I saw the film, it left my heart aching and my brain bemused. The idea that love could reach across time—and just as easily be torn apart by it—felt haunting and profound. The image of a man losing everything by glimpsing a penny from the wrong era was both strange and unforgettable. The movie planted questions that would echo much later in my life: about memory, causality, and fate, but also about how fragile the human condition really is. They are echoing still, as I write this post. It shaped my early understanding not just of science and storytelling, but also of how fragile the human condition really is.

Revisiting Somewhere in Time through the lens of quantum information theory and game theory reveals something remarkable. Richard's seemingly impossible quest, and its heartbreaking end, unexpectedly mirror deep concepts like quantum discord and behavioral strategies under imperfect recall. While the parallels explored in this essay may be striking, they are ultimately metaphorical. This is not a literal mapping of a movie plot onto quantum physics or game theory, but an analogy—a creative lens through which themes of memory, identity, and coherence in Somewhere in Time resonate with ideas in quantum information theory.

Imperfect Recall and the Quantum Solution

In game theory, a key distinction exists between mixed strategies—committing to a complete plan of action in advance—and behavioral strategies, which involve making decisions locally, or in effect, “crossing the bridge when you get to it." With perfect recall by the players or agents, these two approaches are equivalent—a result formalized in Kuhn's Theorem. With this result, an agent can act locally, appearing unpredictable to opponents, while still enacting a preplanned course of action. However, this equivalence breaks down when recall is imperfect, that is, when an agent forgets previous decisions or lacks a complete memory of their plan, leading to coordination issues.

Surprisingly, quantum information offers a solution: even without perfect memory, certain quantum correlations, specifically discord, can restore the coordination typically achieved by classical mixed strategies. Unlike quantum entanglement, quantum discord represents subtle correlations—a hidden coherence between parts of a system that allows them to act in sync, even without direct communication or shared memory. This concept, which I explored in detail in the paper "When Recall Fails, Discord Remembers," (preprint: https://www.arxiv.org/pdf/2505.08917) suggests that an agent using a separable (non-entangled) but discordant quantum state can make local, memoryless decisions and still achieve outcomes consistent with a fully planned strategy. This paves the way for a quantum reinterpretation of bounded rationality, where seemingly irrational or memory-constrained actions can still lead to coherent results.

This surprising possibility—that strategic coherence can emerge even without memory—echoes not only in quantum physics, but in the stories we tell, where remembering oneself can restore a fractured identity. In most myths, tokens given to heroes—rings, amulets, staffs, scarves—serve one core purpose: to remind them of who they are. These objects restore identity, reaffirm purpose, and help the hero stay anchored to their true self through trials and transformations. Remembering is salvific. But in Somewhere in Time, the same mechanism yields the opposite effect. The modern penny serves precisely this mythic function—it reminds Richard of who he is and where he comes from. In myth, such tokens restore unity; here, the same gesture tears coherence apart. The movie inverts the classic arc: remembering does not redeem—it exiles. Identity returns, but at the cost of love.

Richard's Journey: A Quantum Behavioral Strategy

This intriguing game structure aligns remarkably well with Richard's journey. He makes two pivotal decisions: first, to enter 1912 via hypnosis, and second, once there, to sustain or disrupt the illusion (by seeing the modern penny). In quantum terms, the moment Richard sees the penny is like measuring a discordant state using the wrong basis—a kind of internal reference frame that determines how a quantum system is observed. This single act collapses the fragile coherence holding his illusion together, snapping him back into a timeline no longer aligned with his past choices. These actions are made locally, without a conscious, continuous memory of the full timeline or how he arrived. Once in 1912, Richard acts as if he truly belongs, deliberately suppressing knowledge of 1979. His approach is behavioral and deterministic: he makes specific choices at each juncture but doesn't explicitly coordinate them through memory or a grand, pre-set plan.

And yet, the narrative resolves as if a global plan were in place. Elise recognizes him, and the story closes around a curious artifact: a pocket watch that Richard receives from the elderly Elise in 1979 and later gives her in 1912—forming a paradoxical loop with no clear origin. This object, like the penny, plays a symbolic role in reinforcing coherence across time. A seemingly complete timeline emerges from Richard's locally uncoordinated steps. This is precisely where the analogy to quantum discord shines: it enables memoryless, deterministic strategies to yield globally consistent, predetermined-like outcomes.

If Richard had followed a classical mixed strategy, his entire journey would have been pre-committed—a perfectly orchestrated time loop, perhaps achieved through the use of a time machine. But this isn't what we see. Richard stumbles into 1912, improvises his romance, and is unexpectedly yanked back. He doesn't operate with a full plan; he doesn't even have one. Crucially, despite this lack of a classical pre-planned strategy, the outcome is virtually indistinguishable from one that would have resulted from a perfectly coordinated mixed strategy. Somewhere in Time presents a narrative where a behavioral strategy under imperfect recall, remarkably enabled by a kind of emotional and symbolic coherence—the narrative's equivalent of quantum discord—achieves what, in classical terms, only a mixed strategy could.

Conclusion

While Somewhere in Time was certainly not conceived with quantum information in mind, it inadvertently captures a logic remarkably similar to quantum decision-making under severe constraints. What appears to be destiny or fate might, in fact, be the subtle and robust coordination of decisions made without explicit memory—held together not by conventional causality, but by a deeper, underlying correlation. Whether in the realm of quantum physics or the intricate dance of human connection, sometimes, discord is truly enough.

Everyone should watch this film—not just for its aching beauty, but for the strange and profound questions it asks about time, identity, and what it means to remember. And if you're curious about how these ideas play out in the language of quantum theory, I invite you to read my paper on quantum discord and memory (preprint: https://www.arxiv.org/pdf/2505.08917), which inspired this reflection. Sometimes, the science and the story are not so far apart.