Quantum Information, Game Theory, and the Future of Rationality

Quantum Correlations and Their Inherent Causality: What Qadir’s Quantum Economics Foretold

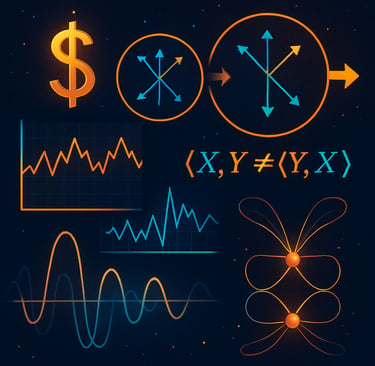

When financial information begins to move through quantum channels, the logic of markets changes. Correlations cease to be mere co-movements and acquire direction — an intrinsic causality born from the order of measurement, the same principle that underlies quantum uncertainty itself. This essay revisits Asghar Qadir’s pioneering idea of quantum economics and explores how measurement, non-commutativity, and quantum information will reshape how we understand cause, effect, and interaction in future financial systems.

Faisal Shah Khan, PhD

11/6/20253 min read

In classical finance, correlation is a symmetrical statistic. If oil prices (X) and the dollar (Y) move together, we say they are correlated—but never that one causes the other. This symmetry underlies everything from portfolio theory to risk management and is mathematically captured by the equation Cov(X,Y) = Cov(Y,X), where Cov stands for covariance.

As a normalized version of covariance, correlation therefore measures co-movement, not causation.

But when financial information becomes quantum informational—transmitted or stored as entangled or superposed signals—this symmetry no longer holds. The order in which information is accessed begins to matter, and that order dependence gives rise to a new kind of correlation: quantum correlation, which is inherently causal.

In 1978, Asghar Qadir proposed that economic quantities might behave like quantum observables, their outcomes dependent on the order in which they are considered. He did not describe this in terms of measurement collapse, but his use of non-commuting operators anticipated the modern view that acquiring information can alter the system being observed. In quantum terms, the expectation value of two observables—say, operators representing oil and dollar prices—depends on their order: ⟨X,Y⟩ is, in general, not equal to ⟨Y,X⟩. This asymmetry arises at the level of expectation values and therefore carries through to the covariance and quantum correlations. In classical statistics such quantities are always symmetric; in the quantum regime, their order-dependence encodes directional information flow, the foundation of what can be called quantum causality.

Quantum computing is already finding early applications in finance—from portfolio optimization to risk modeling—through cloud-accessible processors offered by IBM, IonQ, and others. These efforts reflect a broader shift toward quantum information as a resource for markets: the ability to represent and process uncertainty in fundamentally non-classical ways. The next stage in this evolution is quantum networking, which extends quantum information exchange beyond individual processors to communication between institutions. Banks, exchanges, and infrastructure providers are already testing quantum-secure trading links and data channels, embedding entanglement and superposition directly into market communication. More than two dozen quantum-network environments operate globally in research and pilot form, and early commercial systems have demonstrated real-time, quantum-secure connectivity between financial and research hubs.

In such an environment, measurement is not an abstraction. Every trade, quote, and data query acts as a measurement on the shared informational field of the market. Each act alters that field, meaning that subsequent decisions occur in a different informational state. The market thus behaves as a distributed measurement system, continually collapsing and regenerating correlations through trading activity. Causality arises naturally from this process: it is encoded in the order of information access and action.

This idea reframes what economists mean by causality. In classical econometrics, Granger causality rests on temporal precedence: X causes Y if knowledge of X improves forecasts of Y’s future values. But this notion assumes observation without disturbance, an impossible condition in quantum systems. In quantum information, the act of measurement itself changes the system. Causality therefore becomes structural rather than statistical, measured by the non-commutativity of observables. It is causality without time lags, defined by informational order rather than chronology.

In ongoing work with colleagues, I have suggested that entanglement could act as a public signal in quantum markets, measurable through quantum-data techniques such as tomography. By analogy, order-dependent asymmetries in joint statistics could serve as causal signals—observable indicators of directional information flow. Quantum-data-literate traders might learn to detect these asymmetries, inferring which variable’s measurement reconfigures the informational state of the other. Such causal signals could eventually underpin new classes of instruments, from quantum-correlation derivatives to market strategies built on informational directionality.

As financial data begin to flow through quantum channels, they will inherit quantum-informational properties: superposition, entanglement, and measurement dependence. Classical correlation models, built on symmetry, will no longer describe the informational structure of markets.

Qadir’s early insight—that economics might someday require quantum logic—was not a metaphor. It was a recognition that when information itself becomes contextual, the market ceases to be a passive system of observation and becomes an active participant in measurement. In such markets, causality is not inferred after the fact; it is generated continuously as information is accessed and acted upon. The traders who first learn to read these causal quantum signals will not merely interpret the market. They will, in a real sense, participate in its creation. And that participation is the real quantum advantage: not simply faster computation, but deeper informational access—the ability to exploit the causal asymmetries embedded in quantum correlations themselves.