Quantum Information, Game Theory, and the Future of Rationality

The Core Cooperative: How Qubits Come to Work Together

As quantum computing moves from isolated processors to interconnected networks, the problem of error correction takes on a new dimension. Stability can no longer be engineered qubit by qubit—it must emerge from the relationships among them. Cooperative game theory offers a way to frame this challenge: not as a fight against noise, but as a negotiation of balance among diverse and imperfect components. In that light, error mitigation becomes less about control, and more about cooperation.

Faisal Shah Khan, PhD

10/7/20256 min read

Quantum computers solve problems through principles that have no equivalent in conventional computation. They use quantum superposition, interference, and entanglement to represent and process information in ways that classical bits cannot. Yet the same quantum effects that grant this power also make these systems extraordinarily fragile. A stray photon, a magnetic ripple, or a defect in the substrate can nudge a qubit out of alignment, spreading noise through the system and undermining computation itself.

What if we stopped thinking of qubits as passive victims of physics and started thinking of them as players in a cooperative game, each with differing capabilities, noise levels, and connections, working together toward a shared goal: a computation with minimal error?

This shift in perspective might help solve one of the hardest challenges in quantum engineering, especially as we move toward heterogeneous quantum systems that combine multiple qubit technologies. DARPA’s Heterogeneous Architectures for Quantum (HARQ) program is at the frontier of this effort, and cooperative game theory—the same branch of mathematics used to analyze markets, politics, and social behavior—offers the conceptual scaffolding needed to make sense of it all.

The New Quantum Patchwork: Heterogeneous Architectures

For the first two decades of the quantum-computing race, each platform evolved largely in isolation. Superconducting qubits, used by IBM, Google, and Rigetti, became the early workhorses. They are fast and relatively easy to fabricate using existing chipmaking techniques but decohere quickly and are sensitive to crosstalk and material defects. Trapped-ion qubits, by contrast, are slower but remarkably stable. These are individual atoms, levitated in vacuum and manipulated by laser beams, capable of maintaining coherence for seconds or even minutes. They rarely lose information, but scaling them is a logistical challenge involving complex optics and control systems.

Photonic qubits are elegant and mobile yet difficult to store. Neutral-atom and spin qubits add further diversity, each bringing unique trade-offs in fidelity, speed, scalability, and connectivity. DARPA’s HARQ initiative rests on a simple but revolutionary idea: why choose one platform when you could use several together?

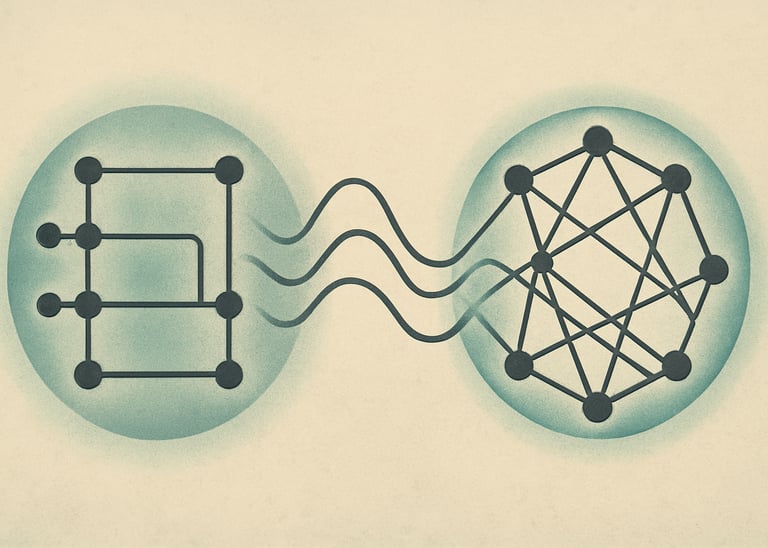

Imagine a network where superconducting qubits handle fast local computations, trapped ions serve as long-lived memory nodes, and photonic qubits act as messengers linking the two. Each subsystem excels at something, but the moment you connect them, the noise landscape becomes uneven. Error rates differ not just from qubit to qubit, but from link to link.

How do you orchestrate cooperation among components that obey different physical rules and whose imperfections are never evenly shared?

The Unequal Game of Quantum Cooperation

Here’s where cooperative game theory enters the scene.

In a cooperative game, multiple players form coalitions to achieve shared benefits. The challenge lies in dividing the collective “payout” so that every participant feels it’s fair and no subset would rather break away to act alone. Translate this to quantum networks: each qubit or node contributes differently to the system’s overall reliability. Some are stable but limited in reach; others are noisy yet strategically connected. Together, they form coalitions—interconnected clusters of qubits whose joint behavior determines the system’s fidelity.

However, cooperation is not automatically beneficial. Consider:

Qubit A: a stable trapped ion that rarely errs but interacts slowly;

Qubit B: a superconducting qubit that is fast but prone to decoherence;

Qubit C: a photonic qubit that connects A and B but adds transmission noise.

If A and B cooperate through C, the outcome could go either way. The bridge (C) introduces noise but also allows redundancy and distributed error correction. Sometimes linking them improves the overall error rate, even if one node—say, B—experiences greater local error exposure. That trade-off, where cooperation benefits the whole but not necessarily each part, is exactly the kind of problem that the core and Shapley value from game theory are built to analyze.

The CORE

While the notion of a core is mathematically elegant, it is not an equilibrium in the usual sense of a fixed point. There is no underlying mapping or best-response function whose solution ensures its realization. Instead, the core defines a feasibility region: the set of payoff configurations where no subset of participants can improve their joint outcome by breaking away.

In the context of quantum networks, this corresponds to a configuration of qubits where no subset could reduce collective error by reorganizing their connections. It represents a form of cooperative stability rather than a dynamical steady state—a condition where every element’s incentive aligns so that no coalition has reason to reorganize. In this sense, the core behaves like an equilibrium, a resting point of incentives, even though it lacks a fixed-point theorem to guarantee its existence or convergence.

The existence of a core depends on a geometric property of the underlying game known as balance, captured by the Bondareva–Shapley theorem. If cooperation exhibits increasing returns—if joining forces always improves collective performance—then the game is balanced and the core is nonempty. But when interactions are uneven or competitive, as in heterogeneous qubit networks, a stable core may not exist: some subsets of qubits will always have an incentive to reorganize for lower error. In such cases, the best we can achieve is to design toward the core, constructing control protocols and feedback rules that approximate this region of cooperative stability even if physics itself provides no guarantee of ever reaching it.

The Shapley Value: Measuring Fair Contribution

Now comes the question of fairness, or in physical terms, contribution.

The Shapley value provides a way to calculate each player’s fair share of the payoff based on how much they contribute when joining different coalitions. In the quantum analogy, it represents how much each qubit adds to reducing overall error or improving fidelity when incorporated into the network.

A trapped-ion node with exceptional coherence might have a high Shapley value because it stabilizes others. A fast superconducting qubit might earn its share by enabling more operations per second. A photonic link might not be stable itself but could have a nonzero Shapley value for connecting distant modules that otherwise couldn’t cooperate. This framework offers a principled way to assess which parts of a heterogeneous quantum architecture are most valuable for overall performance—not by raw physical metrics but by marginal contribution to collective stability.

DARPA’s HARQ: From Engineering to Ecosystem

DARPA’s Heterogeneous Architectures for Quantum (HARQ) program is explicitly funding research to make these mixed systems work. The challenge lies not only in hardware but in architecture and coordination. Different quantum modalities operate at distinct temperatures, frequencies, and control regimes. Bridging them requires solutions for synchronization, noise translation, and state fidelity across interfaces.

HARQ aims to develop the hardware, software, and algorithms that can seamlessly integrate different quantum modalities and minimize error accumulation when information crosses boundaries. That is not just an engineering problem; it is a resource allocation problem, a negotiation problem, and a game-theoretic one. By treating each platform—superconducting, trapped ion, photonic—as a player in a cooperative game with its own constraints and strengths, researchers can use mathematical tools to locate the core of the combined architecture: the regime where adding or removing a subsystem no longer improves overall error performance.

In this sense, HARQ’s ambition is not merely to build a hybrid quantum computer but to make it self-consistent, allowing different qubit species to coexist in a stable coalition.

A New Way to Think About Error Correction

Traditional quantum error correction treats qubits as interchangeable building blocks. Heterogeneous systems demand a new approach: not all qubits are equal, and not all errors weigh the same. A game-theoretic error model could dynamically assign correction duties and redundancy levels based on each qubit’s contribution and vulnerability. Instead of static parity checks, the system could continuously rebalance, like an ecosystem adapting to stress.

If we take the analogy seriously, the quantum processor of the future may look less like a rigid machine and more like a living network—one that organizes itself toward its core configuration, a state of cooperative equilibrium where global error is minimized and local incentives align.

Conclusion: Cooperation as the Quantum Advantage

Quantum computing networks invites a different way of thinking about performance—not as raw speed or control, but as coordination across fragile correlations. Every connection that enables computation also carries the seeds of error, and managing that balance may be the field’s defining challenge.

By borrowing tools from cooperative game theory and aligning them with DARPA’s vision of heterogeneous quantum architectures, we may gain a framework to understand not just how qubits compute but how they collaborate effectively.

In this light, the HARQ initiative is more than a hardware challenge. It represents a shift in how we think about quantum computation: not as a hierarchy of control but as a community of cooperation.

When every qubit’s participation is both fair and essential, the quantum machine will, in a sense, reach its own core—a state where cooperation, not control, becomes the true source of quantum advantage.