Quantum Information, Game Theory, and the Future of Rationality

Yathrib to Medina: Social Dilemmas And Changing Rationality

"Do you believe in God?" This seemingly straightforward question reveals a simplistic intellect, presuming a universal definition of "God"—often one that aligns with the questioner’s own beliefs. A similar fallacy underpins the word "rationality": people often assume it to mean behavior consistent with their own values or those of their society. Such assumptions falter when confronted with unsettling examples—suicide bombers or genocidal regimes, for instance. These actors are not inherently irrational or evil; rather, they operate within their own distinct frameworks of rationality. Game theory offers us an unbiased lens to define rationality, creating a universal framework free from subjective biases.

Faisal Shah Khan, PhD

12/26/20244 min read

"Civilization is what happens between ice ages," said the American philosopher Will Durant. This is a profound thought, but equally profound—if not more so—is the idea of creating a civilization that is truly civil. A defining characteristic of a civil society is that its members look after one another. But what does that really mean in concrete terms, and does it ever truly come to fruition? Was ancient Egypt a civil society? What about Rome? And what about modern societies like the United States and China?

In many respects, yes, all of these examples could be called civil societies. However, conscripting farmers to build the pyramids or holding brutal bloodsports in the Roman Colosseum are exceptions that complicate the picture. Similarly, in the U.S. today, the absence of universal healthcare—a feature many would consider a hallmark of a civil society—raises questions about the nation’s civil character.

Let's define what it means to be civil using game-theoretic concepts. In game theory, we can view the members of society as players or agents in the "game of civilization," where each player's strategy involves contributing value to the society, in exchange for a payoff. This payoff could take the form of currency (salary), social benefits, or both. For example, a mathematician might have the strategy of teaching her discipline to others, and in return, she receives not only a salary but also prestige and a place of honor.

We assume that every member of society is "rational," meaning they play the game of civil society in a way that aligns with their preferences regarding the outcomes. Many people infer from this definition of rationality that players simply want "more" of something rather than "less." This inference is reasonable, as long as we don’t assume we know exactly what that "something" is. For instance, the mathematician might prefer more recognition in the form of honors and accolades, rather than more salary. This preference could seem irrational to business people in the same society, whose preference might be the opposite—favoring more financial rewards over prestige. And the entire dynamic may well be reversed, depending on the individual’s definition of rationality. Worse, a player's rationality may be such that she wants to acquire more of what another player possesses, and this acquisition must happen by any means necessary, including stealing.

The discussion of how to define rationality is not purely academic; it plays a crucial role in social engineering, whether through education, government programs, or business creation and development. A powerful historical example comes from the Arabian Peninsula (modern Saudi Arabia) and the religion of Islam. In its early days (early 600's C.E.), Muslims, persecuted for their social reforms, were forced to flee their homes in Mecca and migrate to the city of Yathrib to the north. There, Prophet Muhammad and his followers successfully established a society based on the principle of prioritizing the welfare of others over oneself. While this idea was not new, echoing the golden rule of "do unto others as you would have done unto you," it succeeded in a remarkable way at this time.

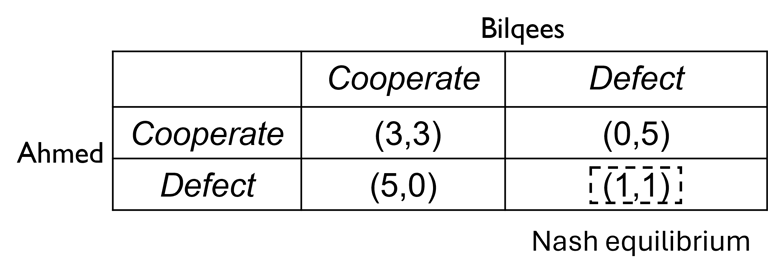

Stories abound of how one member of society gave away a shank of lamb to their neighbor, only to have it returned later in the day after having been sent to many other neighbors. But what does this have to do with the social dilemma? Everything. Let me relate this to the Prisoner's Dilemma, a game in which each player’s rational choice is to act selfishly, seeking a larger payoff rather than a smaller one. While the players (Ahmed and Bilqees here to be culturally appropriate) do not intend to harm each other, their self-interest always leads them to do so if it serves their own benefit.

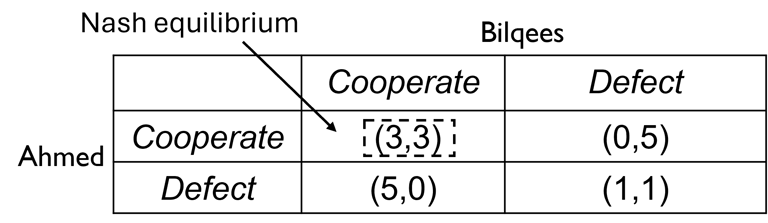

Viewing this simple scenario as a model for society, we see that when everyone acts selfishly, no one truly benefits as much as they could. The (Nash) equilibrium is the suboptimal outcome (Defect, Defect) with a payoff of only 1 to each player. But what if the players were selfless and prioritized the well-being of others over their own? Why would they do this? It is important to note that in the Prisoner’s Dilemma, if players' rationality is redefined so that they seek to maximize the benefit of the other player instead of their own, the dilemma disappears entirely! In such a case, the logic of selfishness no longer applies, and cooperation would naturally lead to better outcomes for everyone.

The lesson here is that when people wonder why players in the Prisoner’s Dilemma act selfishly, even though selflessness would clearly benefit everyone, they are conflating the rational behaviors of selfish and selfless players. The rationality of selfish players demands they act solely in their own self-interest, while the rationality of selfless players requires the opposite—prioritizing the well-being of others. In this context, a selfless player, acting against the interests of a selfish one, may be seen as a "sucker." The key point is that the dilemma disappears only when all players adopt a selfless approach.

It is not necessarily impossible, as the example of Yathrib demonstrates. The concept of civil behavior was so successful at the time that the city was renamed Madinat al-Munawara—"The Illuminated City" or "The Radiant City"—to reflect the high standard of conduct in the new society. However, social engineering can be challenging, as the life of Prophet Muhammad shows, and indeed, the lives of many social reformers throughout history and into modern times. Even when civil societies do emerge, the rationality of selflessness upon which they are based is often easily overwhelmed by the rationality of selfishness. This is why game theorists tend to favor simpler methods, such as extending game features, over attempting to change the underlying notions of rationality. As we have seen in previous discussions, introducing ways to randomize strategies and incorporating referees is a time-tested approach that can lead to better solutions. This approach can often be more effective and easier to implement than attempting social upheaval, no matter how appealing the latter may seem both intellectually and emotionally. In this context, technology has played a remarkable role. We are now witnessing the emergence of new technologies, such as AI and quantum computing, which hold the potential to address social dilemmas in innovative ways.